OUR APPROACH TO BEHAVIOUR CHANGE

1) What is environmental behaviour change?

Scientists have long known that models of human decision-making which assume a perfectly rational human being relying on perfect information are deeply flawed. In reality, people are much more complex and much more nuanced, basing their behaviour not only on objective information and rational considerations, but that they also take account of psychological and practical factors, such as values, beliefs, social norms, and habits. (1)

The study of human behaviour, and how to change ingrained behaviour patterns, is especially important for mitigating climate change as between 20% to 36% of emissions could be eliminated through behaviour change in the areas of household food and energy consumption and personal transportation practices. (2)

Environmental campaigns that seek to change human behaviours cannot rely only on awareness raising and educational initiatives. Psychology and group-based interventions have to be applied too, to help pivot peoples’ behaviours into more sustainable directions.

2) Why focus on environmental behaviour change?

Through their consumption behaviour, households are responsible for a large share of global greenhouse gas emissions. Some studies have estimated that 20-70% of greenhouse gas emissions are related to consumption patterns in households (3), which means that households are key actors in any strategy aimed at reaching the Paris Agreement goals.

To reach those international agreed climate goals, people in richer countries need to reduce their carbon footprint by at least 47% in nutrition, 68% in housing and 72% in mobility by 2030 and over 75% in nutrition, 93% in housing, and 96% in mobilisation by 2050.

Despite the importance and potential of behaviour change, most policy approaches to climate change have paid scant attention to the issue, choosing to focus instead on top-down rules and regulations, and the promotion of technological solutions (4). In reality, most technological advances are as yet unproven at scale and calls for political change are also unlikely to be successful if politicians and civil servants are not sufficiently convinced that the proposed changes are feasible and have widespread public support.

Technological solutions, while having a great potential to mitigate emissions through improved efficiency, often are followed by increased consumption. This situation, where emissions savings through increased efficiency are cancelled out by subsequent negative behaviour changes is known as the ‘Rebound Effect’. Furthermore, technological solutions often focus on the solution to one particular challenge (eg the amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere) while ignoring the inter-dependence of the root causes of the problems they aim to address.

In contrast, political solutions can be more constructive, as regulatory and legislative measures can serve to make certain behaviours, products and processes unattractive, unavailable or socially undesirable. Political change is a powerful factor in behaviour change. However, the causal relationship is complex: political change often follows, instead of leading, societal change. Furthermore, environmental behaviour change studies show that for many individual climate actions voluntarily adopted behaviours are more effective in reducing emissions than enforced environmental action (top-down regulations). One study showed that households reached more of their total reduction (56%) in the voluntary round (36%) than in the “forced” one (20%) (5).

This is also a lesson we learned in GAP’s EcoTeams programme. The EcoTeams programme was born out of Global Action Plan’s focus on achieving societal change through small, incremental actions at community level. Evaluations of the programme, which ran in Ireland as well as in other European countries, showed that the model was highly effective in encouraging voluntary practical lifestyle changes. By designing their own sustainability journeys participants gained confidence and agency and were more likely to maintain changes that were introduced during the project. They were also likely to become advocates for eco-friendly behaviour. (6)

It is this same approach of encouragement and peer support that informs GAP’s programme today.

GAP is convinced that we need to change as consumers,

as members of communities and organisations,

and as citizens who can influence policies.

We all have a role to play, and we all need the support of our peers.

3) What Works?

Human behaviour is largely formed by people’s underlying values. Most people, young and old, are naturally compassionate and care about other people and the environment. However, powerful influences (i.e. advertising, social media, peer pressure etc.) have an impact on what we say, how we act and the decisions we make (7).

When people are surrounded by messages that run counter to their core values, this may result in a belief that it may be socially undesirable to act on one’s core values. This “values-action gap”, based on a mistaken belief that others don’t share many of our key concerns about the environment can lead to a reinforcing spiral of inaction.

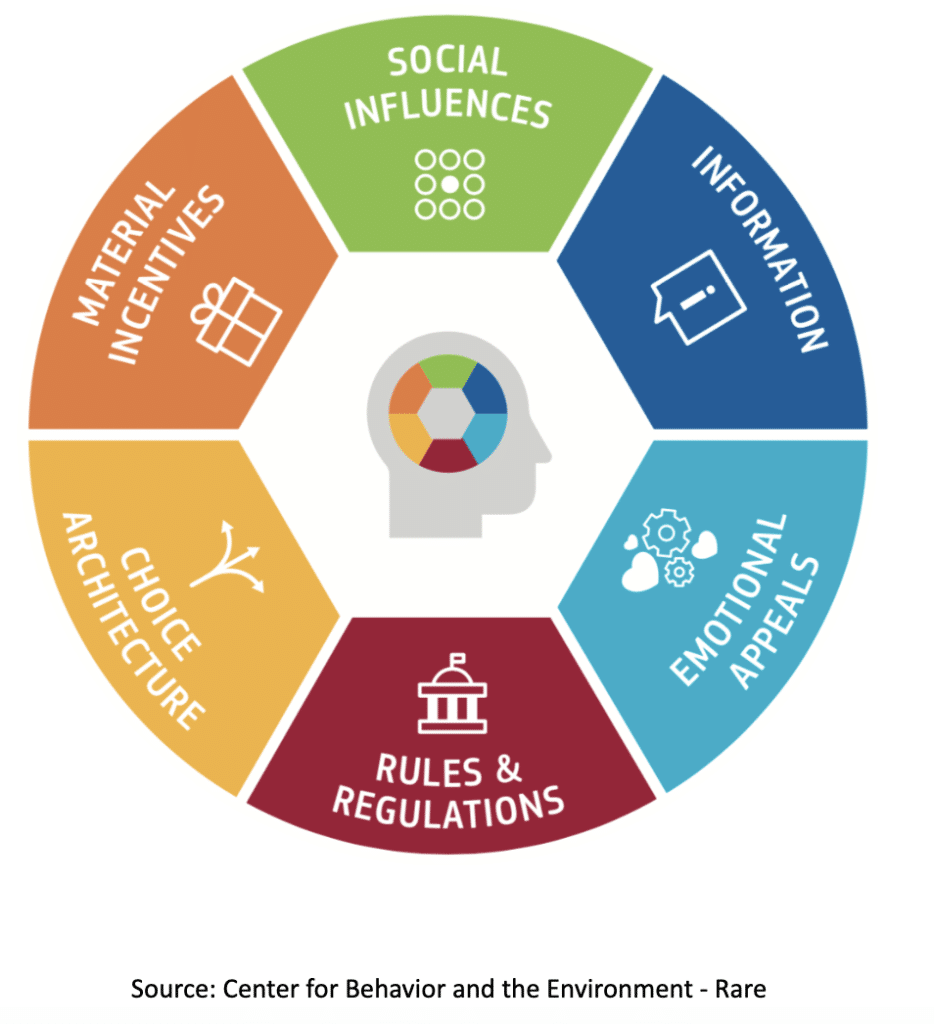

There exist a range of tools that can be used to influence human behaviour, with emotional appeals, social incentives, and choice architecture being the most promising “levers” to influence behaviour.

4) Some core elements in the ‘behaviour change toolbox’:

- Appealing to emotions. Studies show that when people make consumption decisions, the parts of the brain responsible for feelings, memory, and value judgments are highly active, while much of the brain’s centres for analysis are not. Thus, appealing to emotions to influence the decision is a well-recognised marketing technique, which is increasingly used in climate campaigns as well. Emotional states that involve feelings of pride, responsibility and guilt are particularly powerful. (8)

- Shifting social norms. Another powerful behavioural motivator is social norms. Being social animals, humans adapt their behaviour to what they see as socially appropriate for others. Environmental behaviour change studies show that making people aware that others also strongly value the environment can be a critical strategy to motivate climate action, particularly for individuals that are not strongly personally motivated. (9)

- Facilitating choice architecture. Sometimes environmentally motivated people tend to choose less environmentally-friendly options just out of habit or convenience. Using simple nudges and boost techniques (“choice architecture”), such as highlighting vegan options on the menu or setting default appliances settings to energy savers mode, could help people pivot to more sustainable lifestyles.

- Providing information. Informing people about environmental issues and what they can do to help mitigate them is often overlooked as a behaviour change tool. While it is not in itself an innovative psychological method to change behaviour, it serves as a basis for all other techniques. For example, any programme that reinforces biospheric and altruistic values (benefits to others) is contributing to education for the environment.

Choosing the tools that work is context-dependent. Cooperative dilemmas, like littering in public spaces, require shifting social norms; adopting novel and costly practices, like electric vehicles, requires risk reduction through economic incentives; overcoming the intention-action gap in low-cost decisions could be achieved through small nudges in choice architecture strategies, while bigger changes, like switching to a vegan diet, are likely to require strong emotional appeal. (10)

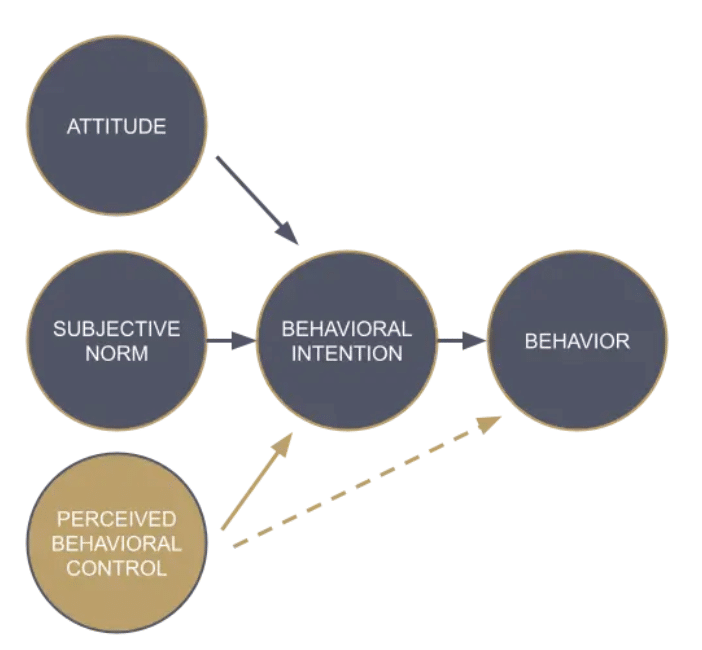

A core focus of GAP’s work is to help people discover their power to make a difference. In behavioural science, and in community work, practitioners have found that people will not make changes in their behaviour if they are not convinced that they have the power to change, or that making the change matters.

GAP’s programmes help improve this “perceived behavioural control” – people’s confidence that they can overcome real and perceived barriers to change – by breaking down big issues into small steps, and by ensuring that people are supported by a network of peers in their communities, be that communities of communities of place (eg. towns, villages), communities of interest (eg. places of work, clubs), communities of circumstance (eg. tenants, people with disabilities) and communities of practice (eg. membership organisations, work teams).

GAP’s approach to behaviour change

Global Action Plan has a long track record of implementing successful behaviour change programmes, and always strives to use an evidence-based approach in its projects. We understand the importance of tracking the impact of our activities, and we make a concerted effort to measure the change that occurs as a result of our interventions. By staying attuned to the latest research and carefully measuring our impact, we can continually improve and refine our approach to behaviour change.

Through our experience, continuous knowledge sharing with other members of the GAP International network, and by basing our work on existing research, we have refined 3 key principles inherent to the behaviour change programmes at GAP:

1. Creating space for experimentation

In our experience at Global Action Plan, and documented in many countries, the single most effective mechanism by which we can promote behaviour change is to give people space to experiment. By trying out new habits, and by being enabled to experiment in a safe and supportive environment, people can go beyond many of the barriers they might have encountered, and experience new opportunities.

Lasting behaviour change can only happen if people are given the opportunity to analyse current behaviour, examine the benefits and disadvantages of old habits, and experiment with alternatives.

2. Investing in people.

GAP is based on the belief in the value of all human beings, and in our abilities to make choices and attain goals. But we also know that societal realities – differences in power, prestige, wealth and physical abilities – mean that many people experience limitations in their ability to make their own decisions.

People’s ability and potential are not fixed, but change over time. Our social, political and economic circumstances can influence our perceived autonomy and ability to act, and our previous experiences, good and bad, can determine our belief in our own ability.

Eliminating or reducing barriers to change, and providing a safe and supportive atmosphere, are important steps in any programme that hopes to change people’s behaviour.

3. Going beyond information provision.

Besides being educational, our projects endorse, nurture, and activate compassionate values in the people and organisations we work with. Through our programmes, we empower people to take action.

Instead of focusing on one-off informational campaigns, or trying to reach as many people as possible, we believe in the power of long-term involvement with smaller groups of target participants. This approach delivers sustained behaviour change and activation of environmental values in communities.

4. Targeting local innovators.

GAP uses the concept that if 10% of the population in a local area completes a team action this can be enough to cause significant change. At GAP we identify and work with local community innovators, to provide them with guidance and tools for change-making.

By supporting their efforts over the long term and making them visible to the local community we push for normative changes at a societal level.

5. Participatory community-driven design.

The people taking part in GAP programmes are not ‘targets’ for behaviour change, but active contributors to the design and implementation of the interventions.

Most people have strong compassion values and care for others and the environment, and our programmes focus on helping people discover others in their communities share their values. We provide guidance and opportunities for people to enable them to design actions and give them agency to construct solutions that are most appropriate to them and their social and natural environment.

Footnotes:

- Williamson, K., Satre-Meloy, A., Velasco, K., & Green, K., 2018.Climate Change Needs Behavior Change: Making the Case For Behavioral Solutions to Reduce Global Warming. Arlington, VA: Rare. Available online at rare.org/center

- Institute for Global Environmental Strategies, Aalto University, and D-mat ltd. 2019. 1.5-Degree Lifestyles: Targets and Optionsfor Reducing Lifestyle Carbon Footprints. Technical Report. Institute for Global Environmental Strategies, Hayama, Japan.

- Eurostat (online data code: env_ac_ainah_r2) estimates that European households were responsible for 21% of total GHG emissions in 2021. However, studies that also account for indirect emissions that are related to household consumption place the figure much higher – at around 70%. For example, Dubois, G. et al., 2019.

- Creutzig, Felix, Blanca Fernandez, Helmut Haberl, Radhika Khosla,Yacob Mulugetta, and Karen C. Seto. 2016.“Beyond Technology: Demand-Side Solutions for Climate Change Mitigation.” Annual Review of Environment and Resources41 (1): 173–98.

- Dubois, G. et al., 2019. It starts at home? Climate policies targeting household consumption and behavioral decisions are key to low-carbon futures. Energy Research & Social Science, Volume 52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2019.02.001.

- Nsmc – Global Action Plan EcoTeams. Available at: https://www.thensmc.com/resources/showcase/ecoteams#:~:text=Global%20Action%20Plan%20provides%20a,as%20the%20household%20feedback%20reports

- A Global Action Plan International Masterclass by Dr Morgan Phillips on “Values led approach to unleashing young people’s potential to do good”, March 25, 2021.

- Stoll-Kleemann, S., 2019. Feasible Options for Behavior Change Toward More Effective Ocean Literacy: A Systematic Review. Front. Mar. Sci. 6:273. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2019.00273

- Bouman, T., & Steg, L. (2022). Engaging City Residents in Climate Action: Addressing the Personal and Group Value-Base Behind Residents’ Climate Actions. Urbanisation, 7(1_suppl), S26-S41. https://doi.org/10.1177/2455747120965197

- Bujold, P. M., Williamson, K., & Thulin, E., 2020.The Science of Changing Behavior for Environmental Outcomes:A Literature Review. Rare Center for Behavior & the Environment and the Scientific and Technical Advisory Panel to the Global Environment Facility.